By Phil Cohen, Jessica DeNisi and Osvaldo Torres

Under the rules of the EB-5 program, an investor must make an “at risk” investment in a new commercial enterprise (NCE) that creates ten full-time positions for U.S workers. The USCIS Policy Manual (Policy Manual) provides that the investor must maintain that investment “at risk” throughout the two-year conditional residence period (the Sustainment Period) in order to remain eligible for a conditional or unconditional green card. As a result, after the initial EB-5 investment is repaid, returned investment funds are generally redeployed into a new “at risk” investment opportunity.

The requirement that the investment be “at risk” can be found at 8 C.F.R. § 204.6(j)(2), requiring that the investment be placed “at risk for the purpose of generating a return on the capital placed at risk.” The precedent decision, Matter of Izummi, 22 I&N Dec.169 (1998), also addresses the “at risk” requirement. Taken together, the law (regulations and precedent decisions) prevents the deployment or redeployment of invested funds into any investment that guarantees returns or has no chance for gain or loss.

In the Policy Manual[1], updated as of July 24, 2020, USCIS stated that, among other requirements, before the job creation requirement has been met, the investment must also involve a “sufficient relationship to commercial activity (namely engagement in commerce, that is, the exchange of goods and services) exists such that the enterprise is and remains commercial.” After the job creation requirement has already been satisfied, the Policy Manual[2] sets forth additional standards to meet the “at risk” requirement, providing that further deployment must occur “within a reasonable time[3]” into “any commercial activity that is consistent with the purpose of the new commercial enterprise to engage in the ongoing conduct of lawful business.” On July 24, 2020, USCIS updated the Policy Manual[4] to also provide that further deployment must occur through the same new commercial enterprise and within the same regional center, including the regional center’s geographic territory.

WHERE CAN EB-5 FUNDS BE REDEPLOYED?

USCIS explained that “engagement in commerce” is “the exchange of goods or services.” Although it is nowhere defined in any immigration statute, regulation or policy memo, further deployment of the capital into a project that involves the development of existing real property, a common use of EB-5 funds that satisfies the requirements of the EB-5 Program upon initial deployment of capital, would presumably qualify.

The requirement that the redeployment be “consistent with the purpose of the new commercial enterprise to engage in lawful business” is also not entirely clear. However, USCIS gives one example of an NCE that makes an initial investment in a loan for the construction of a residential building, and states that the NCE may make reinvestments in one or more similar loans. There seems to be an implied requirement that the NCE’s company agreement or operating agreement authorizes a redeployment.

For the first time, the EB-5 Reform and Integrity Act of 2022, which repealed the existing EB-5 law and authorized the availability of EB-5 visas for Regional Center investors through September 20, 2027 (the “Integrity Act”) has codified the redeployment requirement. In particular, the Integrity Act provides that investor capital can be further deployed if the NCE has satisfied the job creation requirements for all investors; deployed the investor capital and carried out the proposed project in good faith and in keeping with the Matter of Ho compliant business plan; and the capital is redeployed in a manner that maintains the investment “at risk” in a project or investment that is not “passive,” including bonds. The Integrity Act directly contracts previous USCIS policy in one important area — the provisions of the Integrity Act provides that redeployment can occur outside the territory of the previously designated regional center, a source of contention between USCIS and EB-5 industry stakeholders and the subject of litigation. The Integrity Act also makes it clear that the original project must have been completed without a material change and all of the required jobs must have been created.

Although the Integrity Act clearly displaces USCIS Policy as to any geographic restrictions for redeployment, it also mandates that USCIS promulgate regulations to implement the Integrity Act’s provisions, creating some ambiguity as to the application of the new rule. As of April 2022, the USCIS website states that USCIS’ previous geographic restrictions will not apply to previously filed petitions,[5] but the USCIS website is certainly subject to change.

The Integrity Act also notably provides that redeployment in violation of the Integrity Act will result in the termination of the Regional Center. USCIS previously stated that the termination of a regional center constitutes a material change that could render an investor ineligible for a green card, making compliance with the reemployment requirement more important than ever.

The Integrity Act does not address USCIS’ position that the redeployment must take place within a certain time frame, nor does it provide further clarification on the type of business that would qualify for an appropriate “at risk” investment, leaving the EB-5 Industry with lingering questions and the hope for additional clarification sooner rather than later particularly given the harsh new consequences for noncompliance.

REDEPLOYMENT IMPLICATIONS FROM A SECURITIES PERSPECTIVE

Because the new sustainment period under the Reform Act does not appear to apply to pre-Reform Act investors, redeployment requires careful consideration. Redeployment is a complex matter, mainly because it creates tension in the investor relationship and poses legal risk for those principals charged with steering a redeployment solution. As such, redeployment presents peril. If redeployment is not effected in a timely manner, the immigration benefit is put at risk; if it is effected with self-interest, or is sloppily or not properly treated, it opens the door to claims of fraud, if not diversion. All of this would likely lead to securities law liability.

There are many practical steps that must be undertaken to process a redeployment strategy. The first stop takes us to the state of the applicable offering and loan documents. Before 2015, most offering documents did not likely contemplate redeployment because that problem had not yet become a concern. Even before, it had become common to include two-year extensions of the normal five-year loan term because it was understood that processing delays could impact the deals. In any event, we must analyze how the offering documents dealt with redeployment–if at all. There are four potential disclosure scenarios, which go from worse to probably best. These are:

Scenario A: silence, nothing at all on redeployment;

Scenario B: addressed redeployment but relied on investor consent;

Scenario C: NCE fund managers were granted the power to redeploy but no specific targets or parameters were identified; and

Scenario D: NCE fund managers were empowered to redeploy and provided for a plan on redeployment, including identifying targeted projects or at least committed to only redeploy into projects that met certain loan and underwriting parameters likely similar in risk profile to the original investment.

Scenario D may present the best scenario for the NCE principals because it clearly provides the principals with the apparent power and authority to redeploy and invokes investor “buy-in” as to the redeployment parameters. In this scenario it could be argued that no investor consent is needed and that quite possibly only notice of the redeployment is required or desirable and disclosures akin to an offering are not necessary.

As you examine the three other scenarios noted above, one should conclude that investor consent and offering styled disclosures regarding the proposed redeployment are necessary and unavoidable. And if you must obtain investor consent, then the entire process could be imperiled because you might not be able to obtain the needed investor consent that may be required by the applicable operative agreement. This could result in the worst outcome possible: investor denials. Interestingly, too, if the Fund structure was a limited partnership arrangement, the limited partners that are involved in the consent issue could find that by (i) acting they eroded the limited partner liability protections they once enjoyed and (ii) failing to agree, they could subject themselves to liability from other investors as a result of their failure to reach consensus and blowing the redeployment opportunity.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND REDEVELOPMENT

The issue of corporate governance is important even in the case where the offering documents were well prepared.

As fiduciaries, corporate directors, managers and general partners owe their entities, and their shareholders, members or limited partners, the fiduciary duties of care (or diligence) and loyalty (or fidelity) in performing their corporate duties. As noted by the Delaware Court in Shoen v. SAC Holding Corp.: “In essence, the duty of care consists of an obligation to act on an informed basis; the duty of loyalty requires the board and its directors to maintain, in good faith, the corporation’s and its shareholders’ best interests over anyone else’s interests.” As such, it is not surprising that lawsuits asserting corporate misconduct are likely based on alleged breaches of the duty of care and/or the duty of loyalty. However, because the relationship between the Fund managers and the NCE is largely based on contract (that, is the LP or LLC agreement), the first thing we must do is review the applicable operative document to ascertain what duties are owed and if any have been permissibly waived. At least, you can be sure that a litigator will certainly start there and so should we. And hopefully the problem will not be compounded where there is a waiver of the duties that is buried in the documents, raising an adequate disclosure or even adequate waiver issue.

Importantly, it should be noted that absent self-dealing, there should be few limits as to the NCE manager’s selection of a redeployment project. But what does this mean? Well, by being careful and acting on an informed basis (in other words by exercising its duty of care), the NCE manager may have plenty of latitude on its redeployment plans. On the other hand, if the NCE manager has a conflict of interest (think duty of loyalty), then one can be assured that the “conflicted” redeployment choice will be subject to heightened scrutiny.

THE ROLE OF THE NCE MANAGER IN REDEPLOYMENT CASES

In addition to ensuring that the corporate and offering documents provide the needed authority to redeploy, the NCE manager should still seek further protections and assurances to enhance the possibility that it will be shielded from redeployment related liability. This it can do by relying on the advice and opinion of professionals it has engaged. If done correctly, the NCE manager may have the protection afforded by the ever-important business judgement rule.

The business judgment rule is not a standard of conduct, but rather a defense the NCE manager may raise; it is a standard of judicial review of corporate conduct. In other words, the business-judgment rule insulates directors from liability so long as the directors acted in good faith, without conflicts of interest, and did what they believed to be in the best interest of the corporation. As the court in Berg & Berg Enterprises v. Boyle found, “the business judgment rule has two components—immunization from liability …. and a judicial policy of deference to the exercise of good-faith business judgment in management decisions.” The rule requires judicial deference to the business judgment of corporate directors so long as there is no fraud or breach of trust, and no conflict of interest exists.

But as noted, the business judgement rule becomes inapplicable where there is a conflict of interest and instead the “entire fairness standard” may come into place. According to the Delaware Chancery Court [in Encite LLC v. Soni, C.A. No. 2476-VCG (Del. Ch. Nov. 28, 2011)], under this standard the burden is on the director defendants to establish “to the Court’s satisfaction that the transaction was the product of both fair dealing and fair price.” Although fair dealing and fair price concerns are separate lines of inquiry, the determination of entire fairness is not a bifurcated analysis. Citing recent cases, the Delaware Chancery Court acknowledged that “at least in non-fraudulent transactions, price may be the preponderant consideration. That is, although evidence of fair dealing may help demonstrate the fairness of the price obtained, what ultimately matters most is that the price was a fair one.” The Delaware Chancery Court further explained that the entire fairness analysis requires a transaction to be objectively fair and that “the board’s honest belief that the deal was fair is insufficient to satisfy the test.”

Fair dealing cannot be established simply by reliance on expert counsel. That is, although “reasonable reliance on expert counsel is a pertinent factor in evaluating whether corporate directors have met a standard of fairness in their dealings with respect to corporate powers, its existence is not outcome determinative of entire fairness.” So, what is the point here? Even if the deal was fair, the Court could still award damages because a better process might have resulted in a better deal.

HOW THE INTEGRITY ACT AFFECTS AVAILABLE OPTIONS

An NCE’s redeployment options have now shifted in light of the Integrity Act. While some may view it as advantageous to redeploy EB-5 capital to subsequent ‘new development’ projects, over time it is expected that all EB-5 stakeholders, including EB-5 investors, agents and the NCE itself, will come to appreciate that the no longer requiring job creation opens the opportunity to redeploy to lower-risk options and/ or to diversify deployment among several different investments.

In interviews with industry stakeholders, three approaches to redeployment have been commonly seen to date:

- Extending the initial loan to the original developer for the same project

- Arranging a new loan to the prior developer for a similar, new project

- Arranging a new loan to a new developer engaging in a new project similar to the original

Among these options, extending the initial loan to the original developer may or may not be a legally viable option, depending on the legal interpretation of, “at risk” and if and how the funds are technically used. The other two options involve investing capital in new ‘similar’ projects to the original EB-5 project. By definition, however, this option would likely imply “job-creating” investments which in turn implies a higher risk to the EB-5 investors, because job creation typically comes by the construction of a large project and/ or the launch of a new business.

The Integrity Act, in eliminating geographic restrictions from redeployment, re-opens the path to making diversified loans directly to borrowers, via private lenders, or via professionally-managed private credit funds. Without the need for a ‘nexus’ to job creation, EB-5 funds can now be redeployed to already cash-flowing projects for further risk reduction. Examples may include making loans to stabilized businesses with collateral and cash flow, such as already-constructed real-estate developments for renovations, or businesses looking to fund machinery purchases for expansion. Of the options above, only working with a professionally-managed fund reduces the NCE’s responsibility in sourcing, evaluating and ordering due diligence on potential investments. If private fund managers who can deliver 6%-8% (after fees), on well-collateralized loans, and who have themselves have passed independent due diligence, the argument becomes a compelling one for all stakeholders.

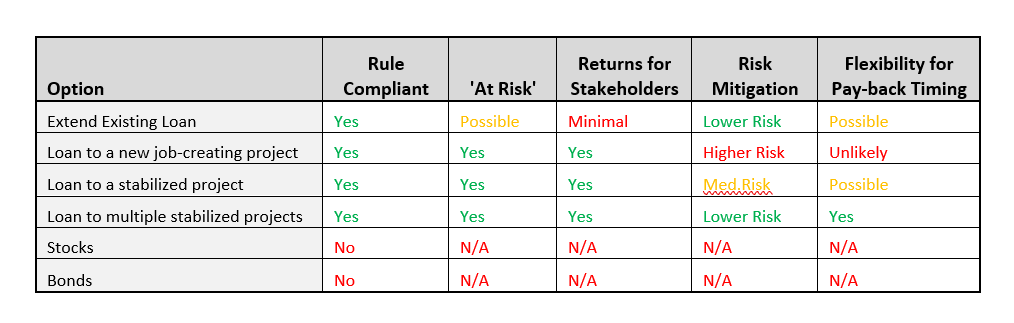

The following table presents an overview of the pros and cons of the various approaches to redeployment.

With some careful research and due diligence, NCEs can explore redeployment options that can generate market-competitive returns, reduce investor risk, and ultimately preserve and enhance the reputation of regional centers, by presenting win-win solutions for all stakeholders.

Because a good portion of EB-5 deals involve affiliated structures where the same principals control both the NCE and the JCE, in other words a conflict of interest is present, then the entire fairness analysis informs us that the “process” matters. As such, quite simply, as a manager making a redeployment decision, you will want to make sure that you have as many arrows in your quiver as possible. That goes to being “informed” and being able to rely on professional advice. For this reason, it is recommended to obtain an opinion from a well-recognized EB-5 immigration firm as to the adequacy (from an immigration compliance perspective) of the contemplated redeployment. While it is very likely that you will not receive an iron clad opinion (what legal opinion is ever iron clad), the opinion may provide the necessary comfort for the manager to proceed. There also may be instances where a valuation or some other independent financial analysis or appraisal should be obtained. The point, of course, being that the manager should arm itself with as much reasonable support for its decision as possible.

—

[1] USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 6, Part G, Chapter 2.

[2] Id.

[3] A reasonable time has been defined by USCIS as twelve (12) months or one year. Policy Manual, Volume 6, Part G, Chapter 2.

[4] USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 6, Part G, Chapter 2.

[5] https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/permanent-workers/employment-based-immigration-fifth-preference-eb-5/eb-5-questions-and-answers-updated-april-2022

—

Jessica DeNisi

Jessica DeNisi is a senior associate with Greenberg Traurig, LLP. DeNisi works with developers and investors who seek to use foreign capital under the EB-5 program to fund job-creating projects as well as E-2 treaty investors. Prior to practicing immigration law, DeNisi worked as a tax and business attorney. She completed her undergraduate studies at Wake Forest University and earned an M.A. in Near Eastern studies from the University of Arizona. She received her JD from Tulane University Law School and a master’s degree in taxation from the University of Washington School of Law.

Osvaldo F. Torres

Osvaldo F. Torres, Esq., a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, has, over his 35-year career, helped clients navigate complex corporate and securities transactions. For the past 12 years, Torres has been immersed in the EB-5 space. He regularly represents regional centers, developers and issuers with offering, loan and redeployment matters for hotel, multi-family, senior living, franchising and other projects. Torres is frequently invited to speak at EB-5 conferences on securities issues. He is a member of the EB-5 SEC Roundtable, serves on IIUSA’s Leadership, Public Policy and Editorial Committees, and is rated AV Preeminent by Martindale-Hubbell.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this article are solely the views of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the publisher, its employees. or its affiliates. The information found on this website is intended to be general information; it is not legal or financial advice. Specific legal or financial advice can only be given by a licensed professional with full knowledge of all the facts and circumstances of your particular situation. You should seek consultation with legal, immigration, and financial experts prior to participating in the EB-5 program Posting a question on this website does not create an attorney-client relationship. All questions you post will be available to the public; do not include confidential information in your question.