By William T. Dean

For most of the past decade, no visa has held the allure of the “golden” EB-5. Now, after several failed attempts at reform and a systemic shortage of available visas, the industry is at a crossroads. Hundreds of would-be EB-5 investors have put their plans on hold. But with proper legal counsel, some of these foreign investors can discover a simpler option they may qualify for: the non-immigrant L-1A, one of the L-1 category visas that provides a faster path to the United States for eligible business executives. With a green card option via conversion to EB-1C, L-1 visa holders who abandon EB-5 can find their ultimate prize simpler and no less golden.

CHANGING TIDES IN EB-5

The prospect of a green card through the EB-5 program once held great social cache. For many high net worth individuals, it was viewed not just as a means of obtaining permanent residency, but as a status symbol. But facing a spiraling waitlist and prolonged uncertainty, many investors — especially those from mainland China, whose filings now atrophy in a nearly 15-year retrogression — are seeking alternatives, both in the United States and elsewhere [1]. In many of these cases, the investors aren’t simply wealthy; they are entrepreneurs, thought leaders or established businesspeople who could contribute to a different national economy immediately. If they meet the criteria to qualify, then the L-1 and EB-1C visa options can reframe their immigration objectives and keep their sights on the United States. At a time when competing citizenship-by-investment programs worldwide are stealing what remains of EB-5’s luster, the L-1 and EB-1C are well worth promoting to candidates who are a match for USCIS’ criteria.

WHO QUALIFIES?

The L-1A is an intracompany transferee visa reserved for executives or managers of foreign companies that have an affiliated or subsidiary U.S. office, or will soon develop one. Not every EB-5 seeker can simply shift gears and pursue the L-1A. On the contrary, if access to significant financial assets is someone’s sole claim to pending EB-5 status, then it’s best to play the USCIS waiting game. But if a visa seeker owns or is employed by an overseas business, has worked in that capacity for at least one year, and performs executive or managerial functions within the organization, he or she may be a prime candidate for the L-1.

There are additional rules, including how recent the applicant’s employment overseas must be (the minimum 12 months of employment must be continuous and all within the past three years), but if an attorney’s review suggests the L-1 is suitable, it should be a less time-consuming route than a standard EB-5 petition. Some applicants could conceivably qualify as either an executive or a manager, depending on how the U.S. entity is structured. However, selecting one path (either executive or managerial) and making a compelling argument for it is the optimal strategy, as USCIS will deny petitions where the roles are unclear.

STRUCTURING THE BENEFICIARY’S POSITION IN A NEW OFFICE

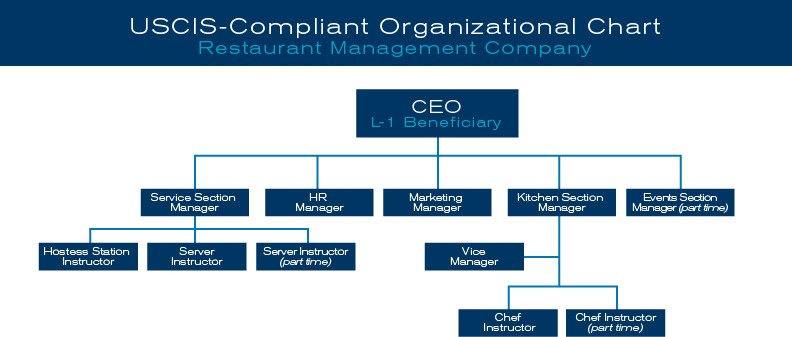

The L-1 visa does not have strict job-creation parameters the way an EB-5 case does. There’s no minimum investment and no requirement that a petitioner be credited with 10 new full-time jobs. That said, the personnel plan is nevertheless an essential component for securing an I-129 approval, especially in a so-called “new office” case where the foreign company has not yet established any U.S. presence. Why? Because paramount to proving that the prospective beneficiary will be either an executive or a manager in the United States is showing a sufficient number of direct reports underneath them — ideally, people who themselves handle advanced business tasks, rather than routine administration or office jobs.

Sketching out the new organizational chart inside a business plan offers a convenient litmus test. Consider this scenario: A Chinese food company plans to expand into the U.S. restaurant industry and wants to send a ranking executive to oversee this new line of business. In a single-location restaurant, the senior person on staff is likely overseeing frontline employees, like cooks and servers. For USCIS, those duties will not pass muster for an L-1 visa. Instead, the L-1A holder may need to oversee two or more locations (or, in the franchise model, an entire territory) with a middle tier of management in order to convince an adjudicator that they’ll serve in an executive-caliber capacity in the United States.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DAILY DUTIES

While it may seem impossible to pinpoint exactly how much time you dedicate to different types of tasks each week — much less to accurately hypothesize how your attentions will evolve over the course of an entire year of running a business — that’s precisely the level of detail USCIS wants to see. It is important to the successful presentation of an L-1 visa case that the filing materials establish the beneficiary as an indispensable part of the expansion plans, someone whose background, guidance and input are invaluable. As such, it is important crucial to first explain their skill set and outline why the person will be instrumental to the U.S. office, in addition to providing granular details about the various roles he or she will fulfill in the new entity.

Ideally, as an accompaniment to the I-129 filing, the applicant’s business plan should include a chart showing a percentage breakdown of which executive-tier tasks this person will perform. Even if this feels like intelligent guesswork — and it typically is, in the case of a new office — this element is critical to the smooth adjudication of an L-1 visa. In a managerial case, identifying the management tasks and the people who answer to the beneficiary will strengthen the case. Either way, there needs to be a clear differentiation between executive-level tasks and managerial-level tasks for both the subsidiary and the overseas company, as USCIS is firm on selecting one or the other.

A BUSINESS PLAN: WHAT DOES IT NEED?

The management summary and organizational charts take on an outsized role in an L-1A, but what else is important to establish? Typically, there is a direct correlation between the foreign company and the U.S. entity. For example, an industrial chemicals company in India that sells mainly to American corporations in the South envisions a stronger U.S. presence by way of a new office in Houston. Here, highlighting the parent company’s track record, product line and recent financial performance is helpful, as is showing where the prospective beneficiary sits in the foreign company’s organizational chart. If the U.S. entity will pursue an unrelated line of business, describing that service or product clearly is the best place to start. From there, a compelling market analysis should show not just the scope of the opportunity, but the state of the industry, the prevailing trends and the competitive forces that the new office will face.

The business plan should also include a marketing and growth plan describing how the new office will flourish under the L-1A holder’s guidance. Next, the personnel plan will function best with descriptions of duties for all supervised employees, as well as a timeline for onboarding. Lastly, photos of the U.S. office can pay big dividends, as will articles of incorporation and details about the lease agreement. For better or worse, at the time of filing, these embellishments take the form of tangible evidence that the applicant’s petition is legitimate.

REQUESTS FOR EVIDENCE

The L-1A is not always smooth sailing, however. Like the H-1B, the L visas have been penalized by the increased scrutiny of USCIS adjudicators since the Trump administration instituted the Buy American and Hire American executive order. Data reveals that requests for evidence (RFEs) and denials have risen steadily ever since 2016, peaking at 51.8 percent and 25.6 percent, respectively, in the first quarter of 2019 [2]. It is very sobering to contemplate that the majority of L-1 filings are now met with an RFE.

Common RFEs question the relationship between the parent and the new subsidiary or affiliate; the applicant’s past employment (length of service or role); or the merits of the planned position in the United States. It is not atypical for an otherwise well-prepared petition to be held up by a boilerplate line of text about the new role or by the minutiae of the intended job in the U.S. enterprise.

By way of example, a recent RFE had, as its root cause, USCIS’ rejection of the idea that the CEO of a company selling religious products would by himself be responsible for determining market prices in the U.S. In the adjudicator’s view, this was a task beneath his station, even though it was in fact a routine part of his personal to-do list abroad. It was never delegated to a subordinate. A knowledgeable immigration professional will not only know when to clarify and expand on qualifying job duties, but also to determine which job duties are not qualifying. As with any case, expert legal advice and a thorough review of all documentation prior to filing is your best defense against an RFE.

SKIPPING THE GREEN CARD LINE

Viewed through today’s cloudy lens of EB-5, the L-1A has several appealing features. For a modest fee, the premium processing option will condense USCIS’ review window from several months to only 15 business days, giving the candidate an answer almost immediately. If approved, the L-1 holder will be granted one year to get the new U.S. office up and running, with the option to file either a renewal extension for the following year or pursue the EB-1C green card (valid for 10 years). Finally, as a dual-intent visa, there is no prohibition on applying for L-1 status even if an applicant has a pending I-526 petition.

While a business visa offers little solace to an EB-5 investor dead-set on passive investment (and its return), it i’s potentially a great fit for wealthy foreigners who are active international executives. All things considered, despite the hurdles of adjudication here in 2019, the L-1A can be an intriguing alternative for businesspeople from backlogged countries like China, India and Vietnam.

Notes:

[1] https://www.eb5insights.com/2018/11/21/updates-on-eb-5-visa-retrogression/

[2] https://ogletree.com/insights/2019-02-27/uscis-data-confirms-increase-in-rfes-and-denials-especially-for-h-1bs

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this article are solely the views of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the publisher, its employees. or its affiliates. The information found on this website is intended to be general information; it is not legal or financial advice. Specific legal or financial advice can only be given by a licensed professional with full knowledge of all the facts and circumstances of your particular situation. You should seek consultation with legal, immigration, and financial experts prior to participating in the EB-5 program Posting a question on this website does not create an attorney-client relationship. All questions you post will be available to the public; do not include confidential information in your question.