By William Dean

Forecasting EB-5 job creation on regional center projects requires an economist to determine the theoretical impact of construction and other project activities on the local economy. But in most direct investment cases, a petitioner simply needs to model out a reasonable pro forma that includes a personnel plan culminating in 10 qualifying positions per investor within the time frame allotted by USCIS.

For stand-alone projects that typically claim only 10 or 20 jobs, EB-5 seekers and their attorneys have to be sure that the projection in the business plan is sufficient, credible and supportable 2-3 years down the line – in other words, that it fully complies with Matter of Ho by making a clear and comprehensive case for the jobs being forecast. Without the benefit of an economic impact study, this can be no small challenge.

GAUGING WHETHER A BUSINESS CAN SUPPORT 10 JOBS

While pending legislative changes are widely expected to increase investment minimums across the board, currently, the minimum investment for EB-5 is $500,000. This amount applies in any rural area or designated Targeted Employment Area (TEA) where joblessness is high; everywhere else, the minimum investment is $1 million. The EB-5 program was originally designed to incentivize investors and developers to choose a location that is lacking employment opportunities. But a business needs to prove 10 new qualifying jobs per investor regardless of the investment amount or location – there is no geographic or economic exception that loosens that requirement for a direct investor. Therefore, it is imperative that he or she plot out their use of funds and hiring timeline carefully to ensure that the capital they’re investing into their specific type of company can generate and sustain at least 10 full-time positions that didn’t exist before (or, in the rare case of a troubled business, jobs that would otherwise be lost).

Additionally, a direct investor must be mindful that there are major differences in how a business needs to be staffed, even within seemingly similar industry sectors. While an urban supermarket will need more than 10 people on its payroll to operate, a small-town convenience store may struggle to justify this sort of headcount. This is equally true for lodging – a 200-room resort in a tourist destination could never survive with so slim a staff, but a rural 20-room drive-up motel that needs only a manager, desk attendant, and cleaning crew on the books could prove off limits for an EB-5 investor, even if the motel is otherwise a prime candidate and requires $500,000 to open.

Statistics show this is a relevant issue more often than not. How many people does the average daycare, short-haul trucking company, or retail store realistically need to employ? Several of these business models could probably be successful with only six or seven employees working full-time. For every medical complex projecting to hire 40 people with ease, there’s a boutique aviation company or small software developer that needs to think creatively to ensure both a viable operating budget and an EB-5 compliant staffing plan of 10 qualifying jobs per investor. After all, any subscription-based industry research site can reveal what percentage of gross revenue a company should be allocating to personnel, so inflating your headcount at the expense of profit margins (or setting below-market salaries to offset that effect) could be its own red flag for an adjudicator.

RESTAURANTS: A QUICK CASE STUDY

Let’s investigate one of the most common business model for direct investment: restaurants. Think back to your last meal at a decent-sized restaurant with an open kitchen. Who did you see working? A host or headwaiter, several servers and cooks, a busser, and perhaps a bartender? In all likelihood, there was also an executive chef, a wine steward, and additional team members working out of view or simply enjoying a day off.

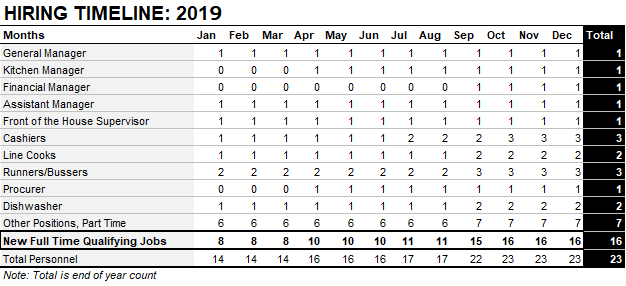

In some cases, a restaurant will open its doors fully staffed; in others, the owners may gradually expand headcount as revenues increase. In this latter scenario, a restauranteur might build out additional seating on a patio to serve more customers, extend the business hours to offer brunch, or move into catering after a successful first year – all decisions that mean hiring new people. Here is the actual personnel table from a new quick service restaurant (QSR), backed by a $1 million EB-5 investor from China and opening its doors to customers in January of 2019:

As depicted in the chart, this QSR will have its grand opening with only eight qualifying EB-5 jobs, but anticipates employing 10 such people by the second quarter, and 16 in total by year’s end. Throughout this startup phase, approximately one-third of all jobs will be part-time positions, giving the restaurant flexibility and some overhead relief without compromising its standing as a suitable EB-5 investment vehicle. Seasonality is a common concern for restaurants and hospitality businesses, but EB-5 investors don’t have the luxury of averaging staff levels; it’s the year-end totals that matter. Importantly, in 2020 (Year 2), this projection continues to show a growing business where the new full-time qualifying jobs remain well above this threshold. In fact, by the middle of 2021, 24 such jobs are forecast in all.

THE CRITICAL FIRST YEARS

This stability in the staffing plan is essential because of the adjudication and review timelines for the investor’s petition. Specifically, an investor must fulfill the USCIS guideline within 2.5 years of the approval of an I-526 filing, proving that all 10 positions exist, or can be expected to exist within a reasonable timeframe, so that conditions hindering permanent residence can be removed. Rather than risk triggering a Request for Evidence (RFE) or Notice of Intent to Deny (NOID), most direct investors shun the conventional wisdom about modeling projections conservatively in order to highlight how completely their business will meet the program requirements and the dictates of the Ho case.

But an overly aggressive staffing plan can be its own liability during the I-829 adjudication if the job creation that was envisioned falls well short of reality. Most often, modeling in a “cushion” – for example, of 12 or 14 qualifying jobs in Year 3 instead of 10 – is a common approach that allows for some natural fluctuation in market conditions and business performance without overpromising or underdelivering. In the case of the restaurant being examined here, had the project site been within a designated TEA suffering from high unemployment, it could actually have supported two separate $500,000 investor petitions based on the qualifying 20+ person headcount reported in the business plan in Year 2 and beyond.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

What else matters about these jobs from a compliance standpoint? To qualify as EB-5 jobs, each position the visa applicant claims to create must be full-time (minimum 35 hours per week) and on payroll, receiving at least minimum wage (state or federal, whichever is higher) and a company-issued Form W-2. Two or more employees can share a full-time job, but they still must be permanent employees who consent to the arrangement and split any benefits that would be granted to a single employee. Additionally, all positions cited as in the plan as EB-5 jobs must be held by people who are work-eligible in the U.S. with a valid Form I-9 and not in the country on a disqualifying visa (including types L, H, or O). 1099 contractors or outsourced/temporary labor cannot count towards total headcount.

To be clear, a business backed by EB-5 funds could theoretically employ a nonimmigrant visa holder, an assistant who works only on Mondays, and even the investor’s own spouse and child – but none of those individuals can bolster the job creation metrics laid out in the business plan for EB-5 purposes. That said, qualified U.S. workers for EB-5 could generally include those granted asylum or refugee status, as well as any lawful permanent resident (LPR) holding an I-551 card. Normally, though, it is the simple things that will help ensure a full personnel plan: if your company hires an answering service, that is an operating expense; if you bring on a receptionist from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. at $12 an hour, you’re creating a job. No matter what the position is, be meticulous with the records you keep: documenting the lawful status of qualifying employees is an extra burden with direct investment, and it is vital to have current I-9 paperwork, annual W-4s, and audited payroll reports at your fingertips.

On the surface, it seems harder to calculate job creation for a large-scale regional center project that tallies indirect and induced labor than to create a “simple” pro forma modeling 10 qualifying jobs for a direct investment case. But a direct investment petitioner who wants to actively manage their business in the United States actually has the tougher assignment. With direct investment, it is not always obvious that a business model will require at least the minimum number of jobs mandated by the EB-5 program. As such, many green card seekers discover that getting to a qualifying 10-person roster within 2.5 years without jeopardizing the bottom line takes careful planning, execution, and even a little creativity. Fortunately for the United States, this approach has proven effective time and again, resulting in I-526 and I-829 approvals for the true creators of permanent jobs: the hands-on investors who opt for direct investment as their path to citizenship.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this article are solely the views of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the publisher, its employees. or its affiliates. The information found on this website is intended to be general information; it is not legal or financial advice. Specific legal or financial advice can only be given by a licensed professional with full knowledge of all the facts and circumstances of your particular situation. You should seek consultation with legal, immigration, and financial experts prior to participating in the EB-5 program Posting a question on this website does not create an attorney-client relationship. All questions you post will be available to the public; do not include confidential information in your question.